Search

Arctic Landscapes and Peoples

Early Arctic Inhabitants

The diverse landscape of the Arctic tundra and ice-covered sea shores has been home to various people and cultures, not to mention some of the most hardy plants and animals, for thousands of years. The earliest human inhabitants of the Arctic were there some 40,000 years ago, even before humans arrived on the North American continent in Alaska.

More Than Just Ice?

Technically speaking the Arctic is the area above 66 degrees and 30 minutes North latitude, and while parts near the North Pole are mostly ice, and endure many months through the years without daylight or nightfall, several cities with more than 30,000 people can also be found in the region. The Arctic landscape ranges from cold and dry deserts to brush and lush tundra plants on permanently frozen soil to icecaps like Greenland’s. Many Arctic coastal areas offer extremely rich habitats bustling with seabirds, fish, marine mammals, and invertebrates.

In the more southern areas of the Arctic, the vast boreal forests full of fir, spruce and birch trees span much of the northern hemisphere and play a critical role in carbon sinks, climate and global cooling. But as you move north, the land becomes treeless. Cold temperatures as low as -60 degrees Celsius, very high wind speeds and a dearth of rain, results in a northern boundary for trees. This "treeline" marks the point where trees can no longer survive such cold conditions.

Life in the Arctic

Despite the cold climate, the Arctic is teeming with life. Although there are comparatively fewer species than in tropical climes arctic ecosystems are characterized by extraordinary concentrations of animals including birds, fish and marine mammals. Smaller animals like wolverines, lynxes, hares and lemmings forage in the tundra. Swarms of pelagic birds like puffins, and auks gather in massive sea-side rookeries while interior lakes and boreal forests are the nursery for many of North America's song-birds and waterfowl. Grizzly bears, wolves and caribou — as well as the curious saiga antelope and musk-ox — inhabit the Arctic tundra. Marine animals like narwhals, belugas, various seals, walruses, polar bears and whales, are found in the cold ocean waters have long been relied upon for food and important resources by all Arctic peoples. The health of these species is becoming increasingly a concern in light of dramatic climate change in the Arctic.

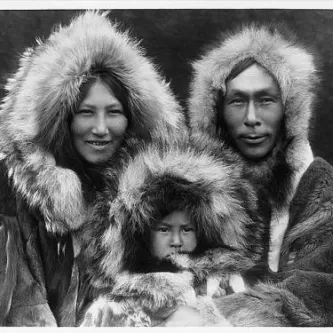

Several groups of people with various cultures live throughout the Arctic, such as the Inuit, Saami, and Nenets. Inuit people whose area extends from Bering Strait to Greenland have more than 100 terms for the various types of snow and sea ice in their native languages. Ethnologist Dr. Igor Krupnik of the Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center (ASC) is helping document valuable traditional knowledge in Arctic communities. His research with Alaskan Natives as part of the International Polar Year (IPY) is also drawing important conclusions into how Native Arctic peoples and communities have adapted and will adapt to climate change in future.

Life for people in the Arctic has meant getting around with snowshoes, kayaks, and skis, and building homes out of whale bone, snow, stone, sod, and driftwood. ASC Director Dr. William Fitzhugh has spent the last decade conducting archaeological field work on hunting and fishing sites in Quebec’s Lower North Shore where the remnants of these homes and tools have shed light on the interactions and adaptations Native Arctic people have made. His work in Labrador, Baffin Island and Quebec over the past 40 years reveals a long, complex history of Indian and Inuit (Eskimo) cultures adapted to climatically-sensitive forest and tundra zones of the Far Northeast as well as to each other and to European newcomers.

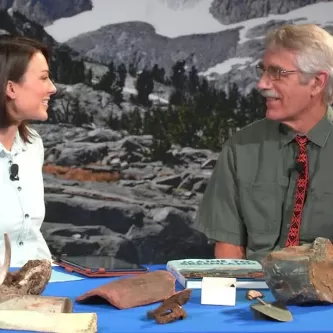

At the ASC in Anchorage, Alaska, Dr. Aron Crowell conducts research in cultural anthropology, archaeology, and oral history. His published findings reflect the importance of collaborations with indigenous communities of the north and with major museums and research institutions. As the curator and project director of the Smithsonian exhibition, "Living Our Cultures, Sharing Our Heritage: The First Peoples of Alaska," he is directing a wide range of current programs in Alaska Native heritage, languages, and arts.

Many Native cultures continue to live in the Arctic today. However their traditional subsistence economies may be jeopardized by climate change, by the lack of educational and employment opportunities in their remote villages, and by the opening of Arctic waters and lands to commercial development. Recognition of the unique relationship between northern people, land and animals has led Arctic Native community members to collaborate with researchers and museum professionals. ASC museum Anthropologist Dr. Stephen Loring has worked with communities across northern Canada on a variety of cultural and heritage initiatives. He has conducted community archaeology projects with Labrador Innu (Indian) and Inuit (Eskimo) young people and has helped facilitate access to the Smithsonian's anthropological and ethnographic collections. The collaborative nature of ASC museum anthropology is apparent in the Inuvualuit Living History project that brought Inuvialuit scholars, elders and youth and museum professionals together to celebrate and document Smithsonian collections.