This collection is based on part of the Objects of Wonder exhibit at the museum. These collection objects illustrate the different reasons some things in nature look blue.

Introduction

The color blue is all around us, but not all blues are made the same. Atomic elements (including those in pigments) and structural colors give plants, animals, and minerals their intense shades of blue. Click on each object below to learn what makes it look blue.

All Color Is Light

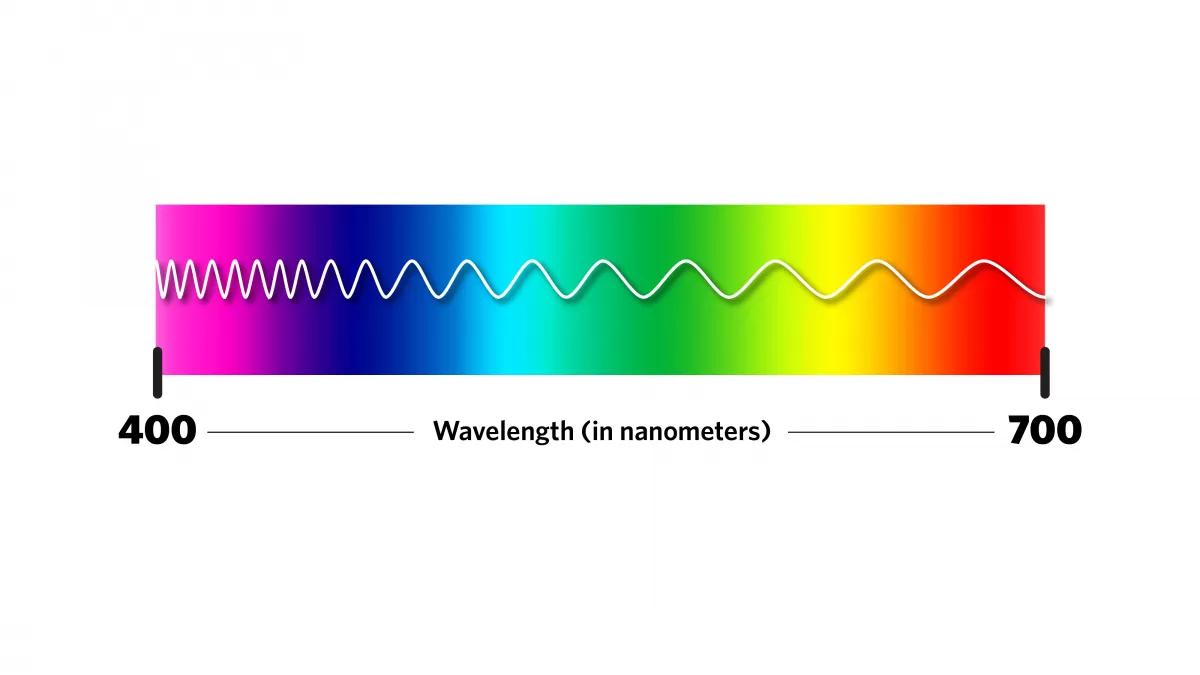

Light is electromagnetic radiation that travels in waves in all directions and interacts with objects. The visible light — what we humans can see — has a wavelength that goes from about 400 to 700 nanometers. A nanometer is microscopic, only one-billionth of a meter, or about 100,000 times narrower than a human hair.

When light hits an object, some wavelengths are absorbed and others are reflected; we see the reflected visible light as color. The color "blue" is light with wavelengths between about 450 and 490 nanometers. Atomic elements and microscopic structures can reflect blue light.

Atomic Elements and Color

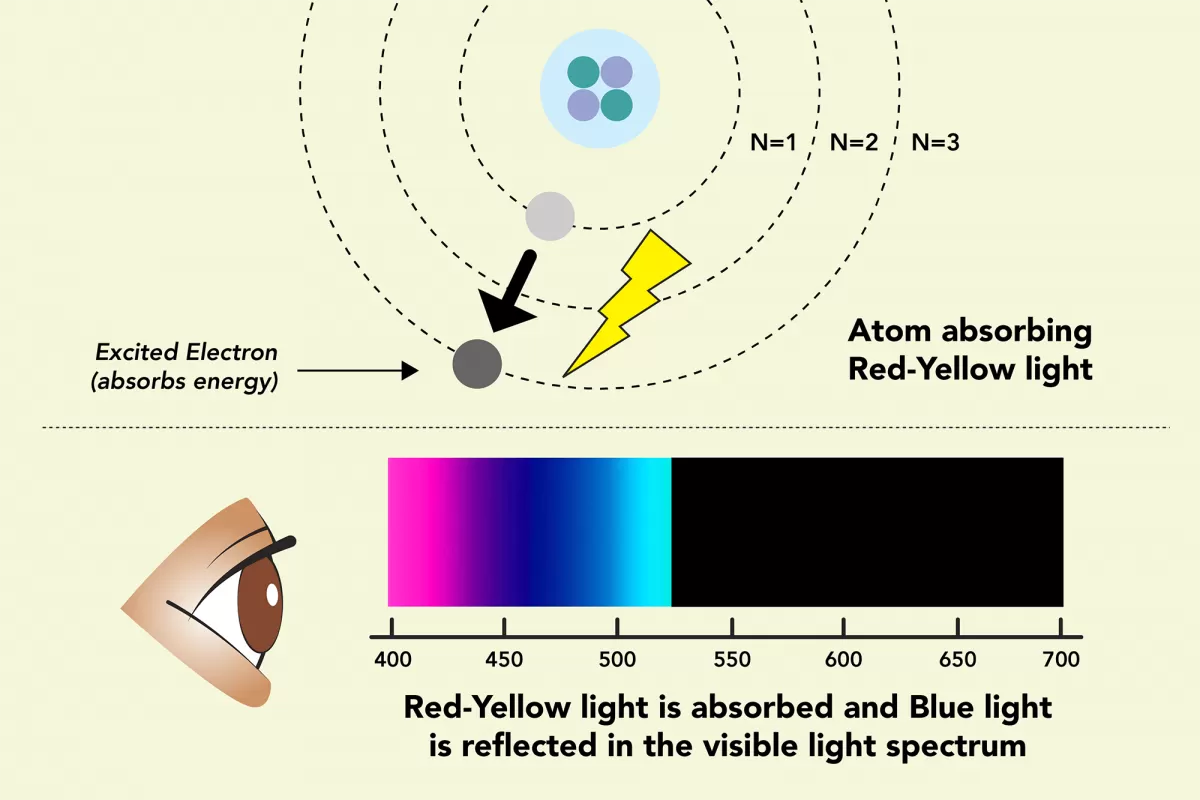

The colors we see are often created by how the atoms in different types of matter absorb and reflect light.

Color in Gems and Minerals

Some gems and minerals are blue because specific atoms or molecules in them reflect blue light. For example, the sulfur atoms in the mineral lazurite absorb yellow and red light, but reflect blue light. Lazurite absorbs yellow and red because those wavelengths have the exact amount of energy to excite the electrons in the sulfur atoms. Those electrons gain energy from the yellow and red light and move to a higher energy level. Blue light has a different amount of energy, so the sulfur atoms reflect it.

The mineral beryl is normally colorless, but beryl containing iron impurities looks blue, because the iron reflects blue light. Blue beryl gems are called aquamarine.

Color in Biology

Biological pigments selectively absorb some colors and reflect others through the same atomic process as gems and minerals — it just happens in pigment cells. An example is chlorophyll pigment in plants — specifically the magnesium atom in chlorophyll molecules — which absorbs red and blue wavelengths of light, but not green wavelengths; those are reflected. This is why most plants appear green to us.

Biological pigments can break down, leading to a change in color. In plants, this is most noticeable in the fall, when leaves rapidly lose their chlorophyll. Some plants produce a pigment, anthocyanin, that turns leaves red when they lose their chlorophyll. Anthocyanin is also responsible for the red in strawberries and the red in red cabbage, among others. Under the right conditions, anthocyanin can also be a blue pigment; it makes the blue in blueberries.

Structural Colors

Structural colors are created by the physical form, or structure, of some plants, animals, and minerals. For example, the Blue Morpho butterfly’s wings have microscopic scales with tiny grooves in them; the grooves amplify blue color reflection, while canceling out every other color.

Another example is the Marble Berry plant (Pollia condensata), which has shiny blue fruits. The blue is created by the structure of the fruit’s cells, which amplify and reflect blue light. You can see a Pollia condensata specimen in the Objects of Wonder exhibit.

As long as the structure is preserved, structural colors don’t fade over time, while biological pigments can break down, leading to a change in color.

Iridescence: Shimmering Colors

Some things change colors when seen from different angles, a characteristic known as iridescence. Soap bubbles, precious opals, peacock feathers, and some insects (including Blue Morpho butterflies) are all examples of iridescent objects.

This effect is a type of structural color and happens when an object’s physical structure causes light waves to combine with one another, a phenomenon known as interference. Depending on the structure’s geometry, the interference either reinforces or dims the initial color. For example, opals are made of microscopic spheres of silica in a very orderly pattern. In some cases, this pattern will cause light waves to interfere one with another, creating a shimmering effect. The microscopic physical structures of some beetles’ shells make them iridescent. Objects made of tiny layers, such as the scales on butterfly wings or the layers of mother of pearl in a mollusc shell, also create these effects.

Related Resources

- Exhibit: Objects of Wonder

- Objects of Wonder StoryMap: The Diversity, Uses, and Geography of Our Collections

- Exhibit: Janet Annenberg Hooker Hall of Geology, Gems, and Minerals

- Video: Butterfly Adaptations – How They Come By Their Colors

- Video: The Beautiful Science of Iridescence (PBS on YouTube)

- Subject Guide: Butterfly Colors and Biomimicry